| |

Anaesthesia and the lung: can oxygen be harmful? |

| |

| Göran Hedenstierna, Uppsala, Sweden |

|

| |

|

| |

Euroanaesthesia 2013, Sir Robert Macintosh lecture on ‘anaesthesia and the lung: can oxygen be harmful?’ was presented by Professor Goran Hedenstierna, University Hospital, Uppsala, Sweden. He used, as the basis for his talk, the paper he has authored in Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica in 2012: ‘Oxygen and anaesthesia: what lung do we deliver to the postoperative ward?’ |

| |

Anaesthetics reduce functional residual capacity (FRC) and promote airway closure. The reason for this is loss of respiratory muscle tone that allows the elastic forces of the lung to pull in the chest wall and to reduce the lung volume. Resistance in the lungs of healthy people can, under anaesthesia, reach those of people with moderate-to-severe asthma. |

| |

Oxygen (O2) is breathed during the induction of anaesthesia, and increased concentration of O2 is given during the surgery to reduce the risk of hypoxemia. However, oxygen is rapidly adsorbed behind closed airways, causing lung collapse (atelectasis) and shunt. Atelectasis occurs to some degree in 90% of anaesthetised patients, and may be a locus for infection and may cause pneumonia. |

| |

Hedenstrierna discussed that post-operative pulmonary complications have been found in 2–20% of patients after non-cardiac surgery, and in a huge retrospective study of 161,000 patients after major, noncardiac surgery pneumonia was found in 1.5%. “This may not seem terrifyingly high, but the mortality was 21% in this group,” he said. |

| |

Measures to prevent atelectasis and possibly reduce post-operative pulmonary complications are based on moderate use of oxygen and preservation or restoration of FRC. Pre-oxygenation with 100% O2 causes atelectasis and should be followed by a recruitment manoeuvre (inflation to an airway pressure of 40 cm H2O for 10 seconds and to higher airway pressures in patients with reduced abdominal compliance (obese and patients with abdominal disorders). Pre-oxygenation with 80% O2 may be sufficient in most patients with no anticipated difficulty in managing the airway, but time to hypoxemia during apnoea decreases from mean 7 to 5 min. An alternative, possibly challenging, procedure is induction of anaesthesia with continuous positive airway pressure/positive end-expiratory pressure to prevent fall in FRC enabling use of 100% O2. A continuous PEEP of 7–10 cm H2O may not necessarily improve oxygenation but should keep the lung open until the end of anaesthesia. An inspired oxygen concentration of 30–40%, or even less, should suffice if the lung is kept open. |

| |

“The goal of the anaesthetic regime should be to deliver a patient with no atelectasis to the post-operative ward and to keep the lung open,” said Hedenstierna. |

| |

He also discussed in his lecture how the critical dependence of atelectasis formation on inspired oxygen concentration increased interest in the pre-oxygenation during induction of anaesthesia. “Again, strong oxygen dependence can be seen. Thus, patients whose anaesthesia has been induced during pre-oxygenation with 100% O2 for 3 min had atelectasis, on average, in 10% of the lung area (corresponding to 15–20% of lung tissue) Pre-oxygenation with 80% O2 for a similar time causes much less atelectasis, with a mean of 2%,” he said. Lower oxygen concentrations reduce atelectasis even further. |

| |

Hedenstierna also discussed the role positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) has in anaesthesia. Because the net effect is that arterial oxygenation is not improved by PEEP, the Nunn group (back in the 1970s) concluded that ‘there is no role for the indiscriminate use of PEEP in routine anaesthesia’. Rather, says Hedenstierna, it may be looked at as a tool for post-operative care than for optimising intraoperative gas exchange. |

| |

Suctioning of the airways also covered, and Hedenstierna believes this process may promote atelectasis formation in addition to other harmful effects. “It is my opinion that the airway suctioning and post-oxygenation do more harm than benefit and is highly questionable. At least, there should be a clear indication for it.” |

| |

Hedenstierna made a number of conclusions/recommendations: |

| |

| Pre-oxygenation with 100% O2 should be followed by a recruitment maneuverer (see point 2) to reopen collapsed alveoli, or induction of anaesthesia can be done with CPAP/PEEP to maintain FRC (that would allow 100% O2 with no atelectasis formation), alternatively. Pre-oxygenation with 80% O2 may be possible in the lung-healthy, non-obese patient with no anticipated difficulty in airway management, followed by a gentle inflation of the lung (shorter apnoea tolerance time but easier to open closed airways than collapsed alveoli). |

| Recruitment by inflation of the lung to an airway pressure of 40 cm H2O for 10 seconds in lung-healthy, normal-weight patients and to higher airway pressures in patients with reduced abdominal compliance (obese and patients with abdominal disorders) after pre-oxygenation with 100% O2 and every 30 min, or a continuous PEEP of 7–10 cm H2O. |

| Low inspired oxygen concentration, 30–40% or even less, if no need of higher concentration. |

| High inspired oxygen concentration shall be given only together with PEEP. |

| Post-oxygenation with or without a recruitment manoeuvre and with or without airway suctioning should not be done routinely but on indication. |

| Deliver a patient with no atelectasis to the post-operative ward and keep the lung open. |

|

| |

|

| |

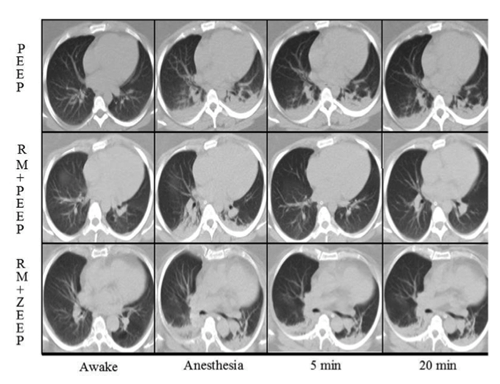

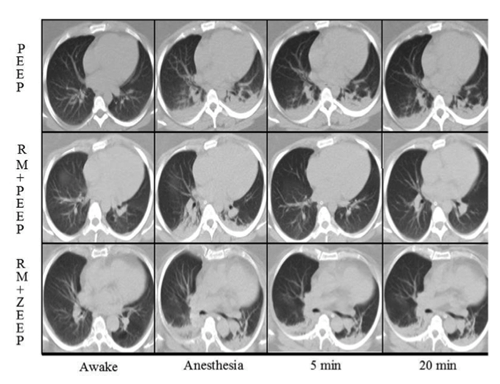

Figure: CT in anaesthetised obese patients. The first row of images show the patients awake and spontaneously breathing, the next after induction of anaesthesia where atelectasis readily forms.

As seen in the top image series, PEEP had no effect on the amount of initial atelectasis. In the two lower image series, a recruitment maneuver (RM) was done right after induction. In the middle series where RM was followed by PEEP, atelectasis was reduced and the effect was sustained for 20 min. In the bottom image series with zero PEEP (ZEEP), the RM caused a temporary reduction of atelectasis, but this effect was gone already after 5 min.

|

| |

References : |

| |

1.Sir Robert Macintosh lecture: Anaesthesia and the lung: can oxygen be harmful? - Göran Hedenstierna, Uppsala, Sweden. Euroanaesthesia 2013, Barcilona, Spain. |

| |

2.Oxygen and anesthesia: what lung do we deliver to the post-operative ward? Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica, Volume 56, Issue 6, pages 675–685, July 2012 |

| |

|